Maps

American Civil War

- Northern states enjoyed a growing majority in the House of Representatives in the decades before the Civil War. But in the Senate, each state gets two votes, regardless of population. And from 1800 to 1850, there were always at least as many slaveholding states as free ones, giving Southern states an effective veto over anti-slavery legislation. But the westward expansion of the United States threatened to upset the balance, as many of the states seeking admission into the Union were not well-suited to slaveholding plantation agriculture. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 temporarily preserved this balance by admitting Missouri as a slave state. But an effort to paper over this conflict again in 1850 was less successful. During the 1850s, the struggle over whether to allow slavery in new states — especially Kansas — started to tear the nation apart.

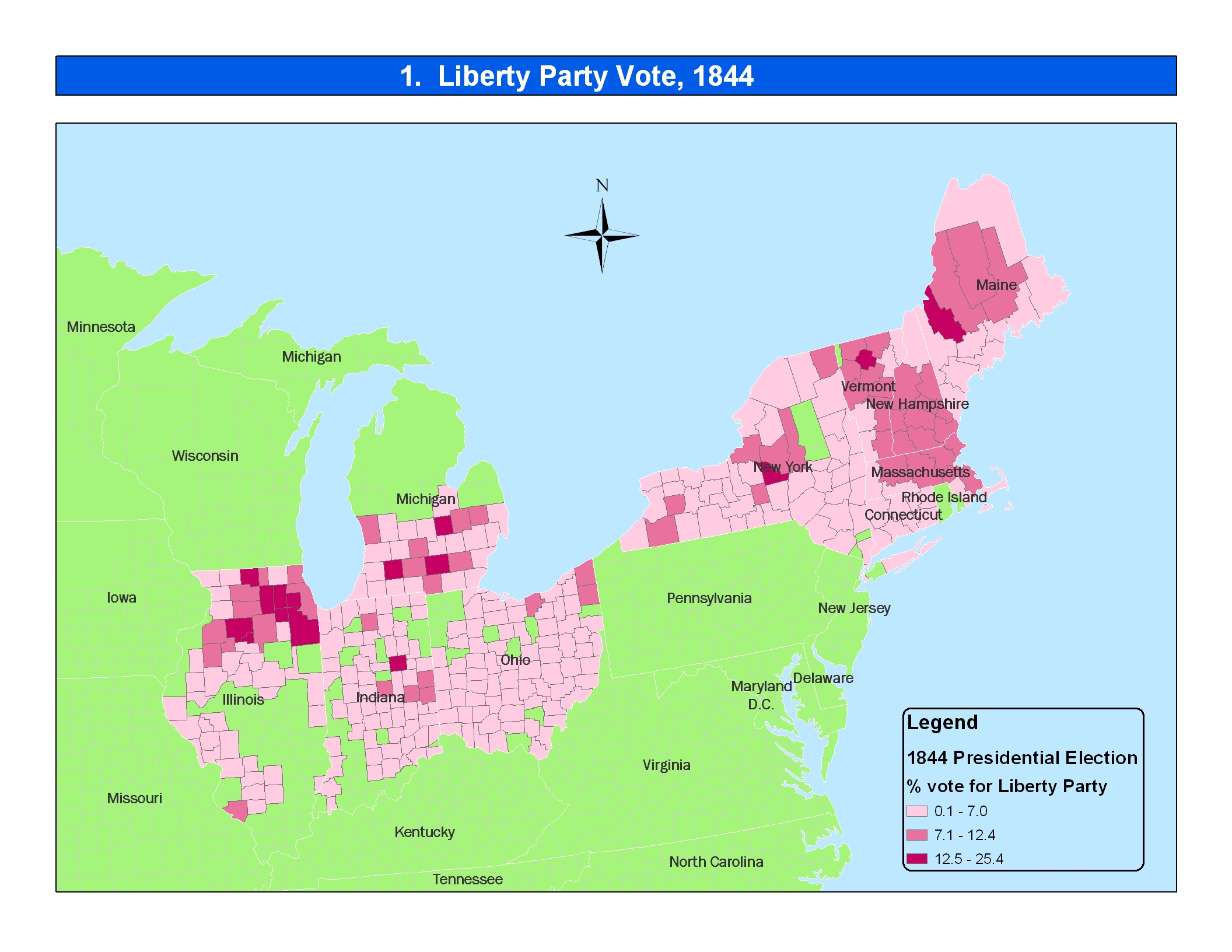

- By the end of the Civil War, the abolition of slavery was a fairly popular position in the North. But it was considered a much more radical position a couple of decades earlier. In 1840, the newly formed Liberty Party endorsed Kentucky lawyer James Birney for president; he got fewer than 7,000 votes. This map shows the results of Birney’s second presidential run in 1844. He garnered 62,000 votes, or about 2 percent of votes cast. Even in the abolitionist strongholds like Massachusetts and New Hampshire, Birney only got about 8 percent of the vote. But support for abolitionist ideas would soar in the North over the next two decades.

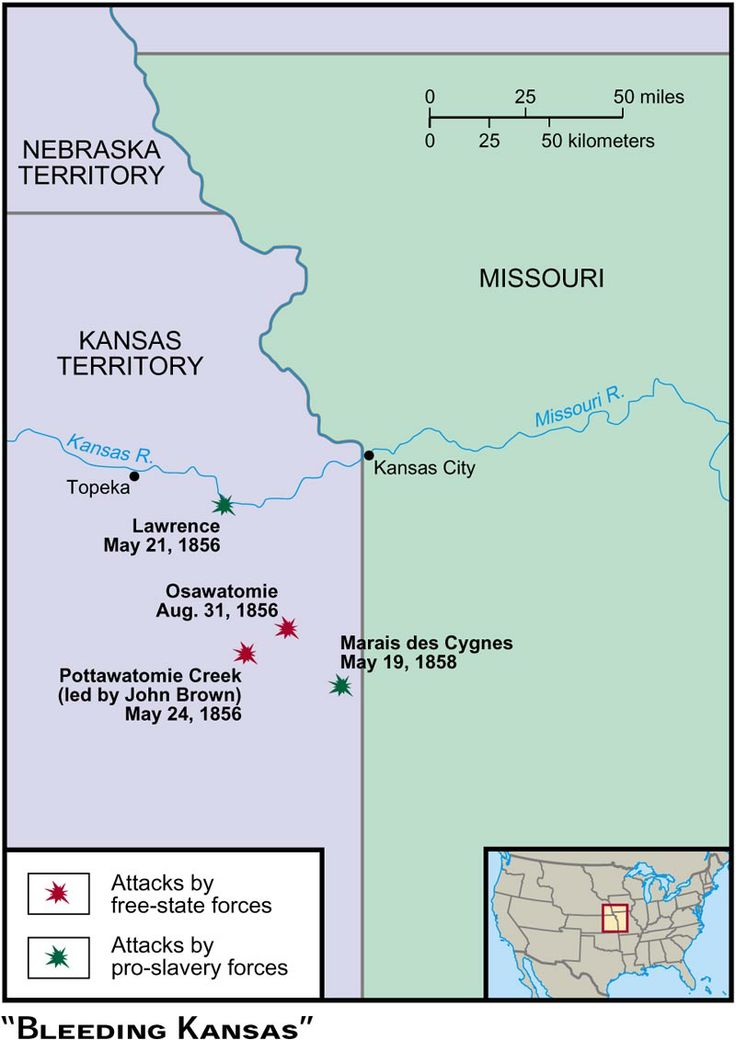

- In the 1850s, Kansas was poised to be admitted as a new state, provoking a dispute over whether it would be a slave state like neighboring Missouri or a free state. In the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, Congress decided that this question would be determined by (white) voters in the sparsely settled territory. Abolitionists began moving to Kansas in hopes of creating an anti-slavery majority there. Missouri residents in favor of slavery crossed the border to cast illegal votes for a pro-slavery legislature in 1855. They also launched violent attacks on abolitionist settlers, which triggered reprisals from the abolitionists. This fraud and bloodshed radicalized Northern voters, making them more willing to countenance aggressive measures to stop the expansion of slavery, even if doing so antagonized the South.

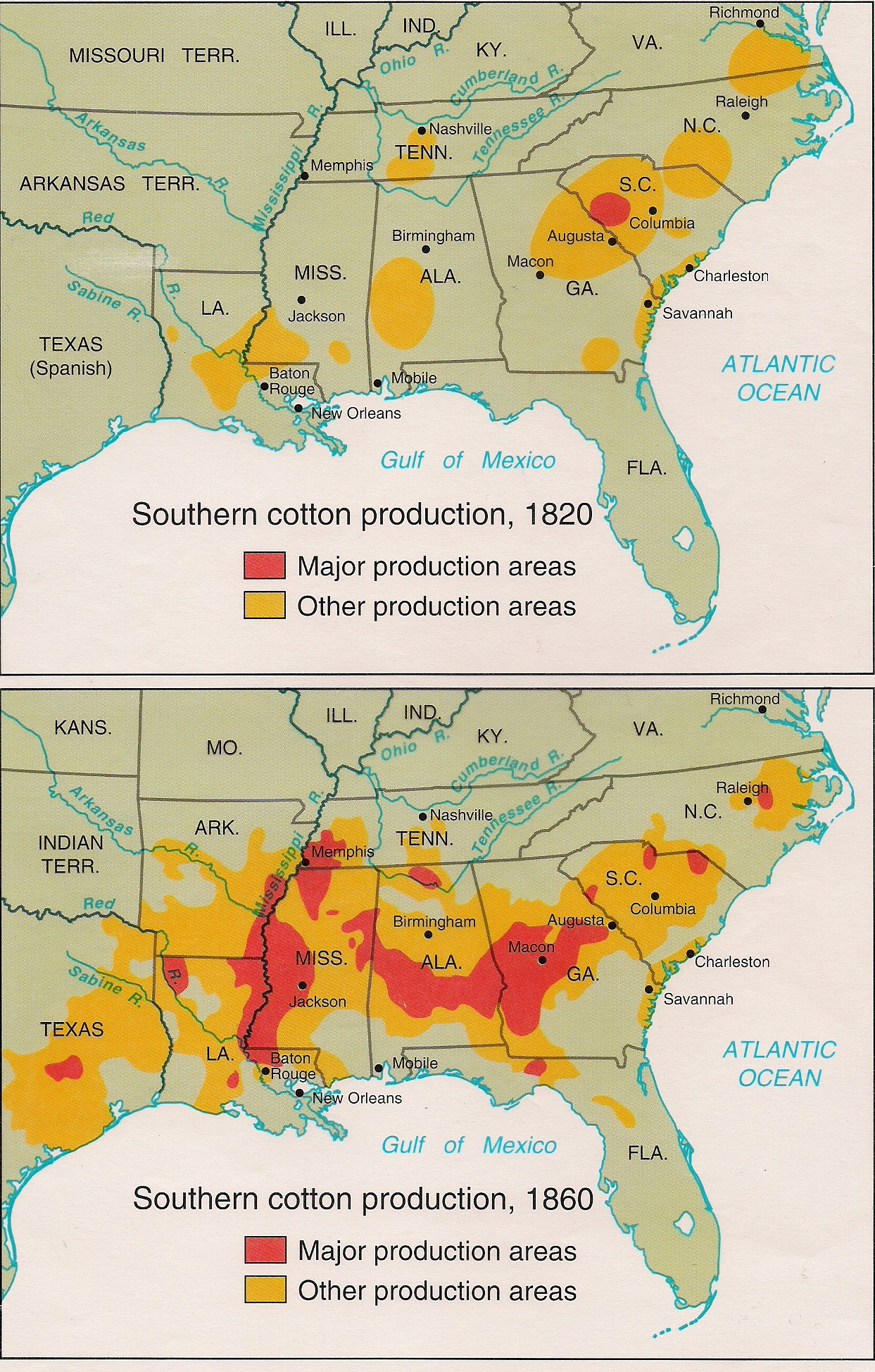

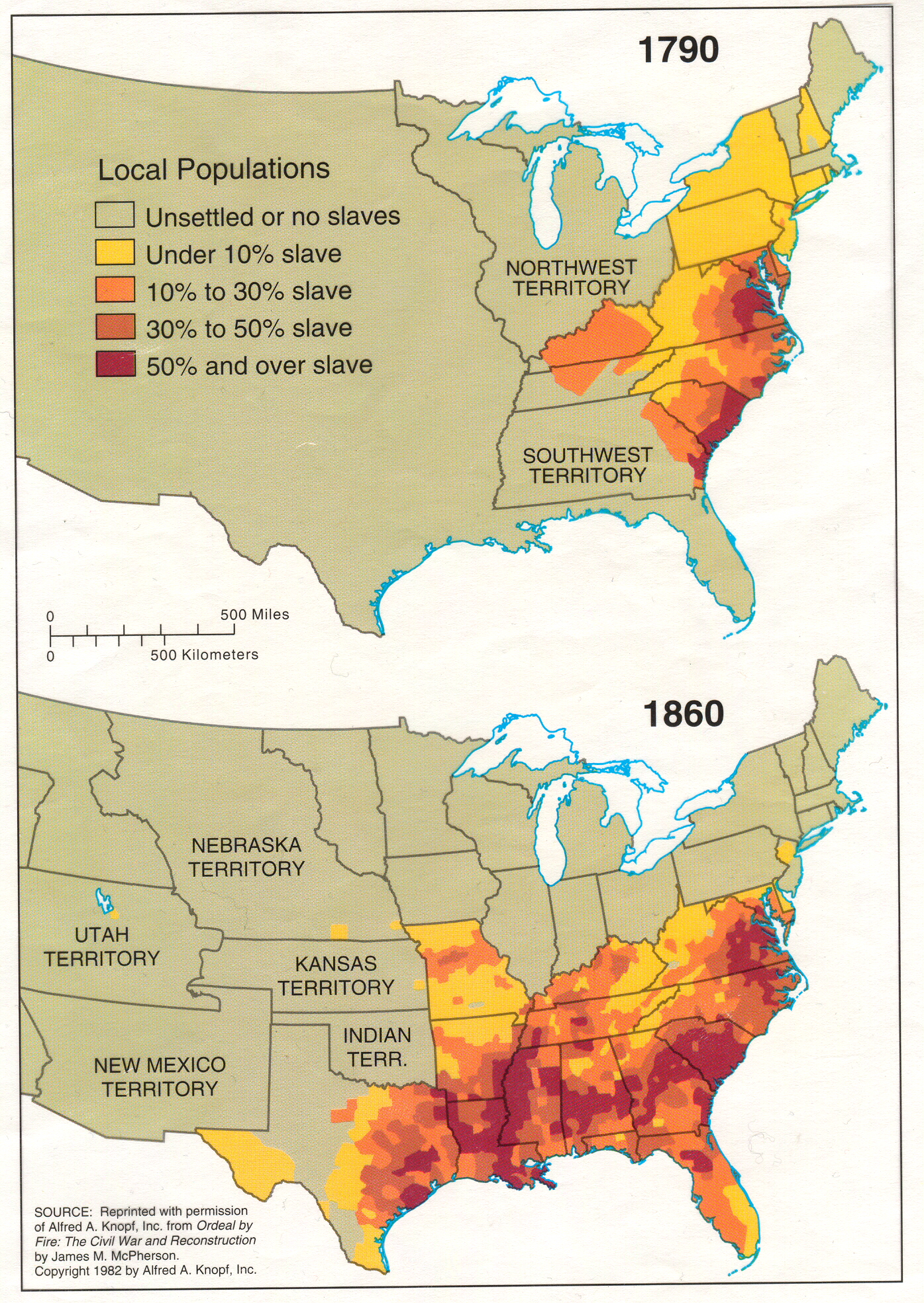

- The early 1800s were a time of rapid progress in weaving technology. And as the textile industries in Britain and New England boomed, demand for cotton surged. That boosted the economy of the American South, whose warm, moist climate and fertile soils were well-suited to producing cotton. This map shows how the South responded in the four decades prior to the Civil War. Cotton production expanded and intensified from Texas to North Carolina, and from Tennessee to Florida. By 1860, cotton comprised 60 percent of American exports, and almost all of it came from the South.

- It’s not a coincidence that this pair of maps looks so similar to the cotton maps above. Vast Southern cotton plantations relied heavily on slaves for the menial work of planting and harvesting cotton — so growing demand for cotton meant growing demand for slaves. Meanwhile, things were trending in the opposite direction in the North, where small-scale farms and industrialization limited the value of slave labor. So the United States became increasingly divided between an enslaved South and a free North.

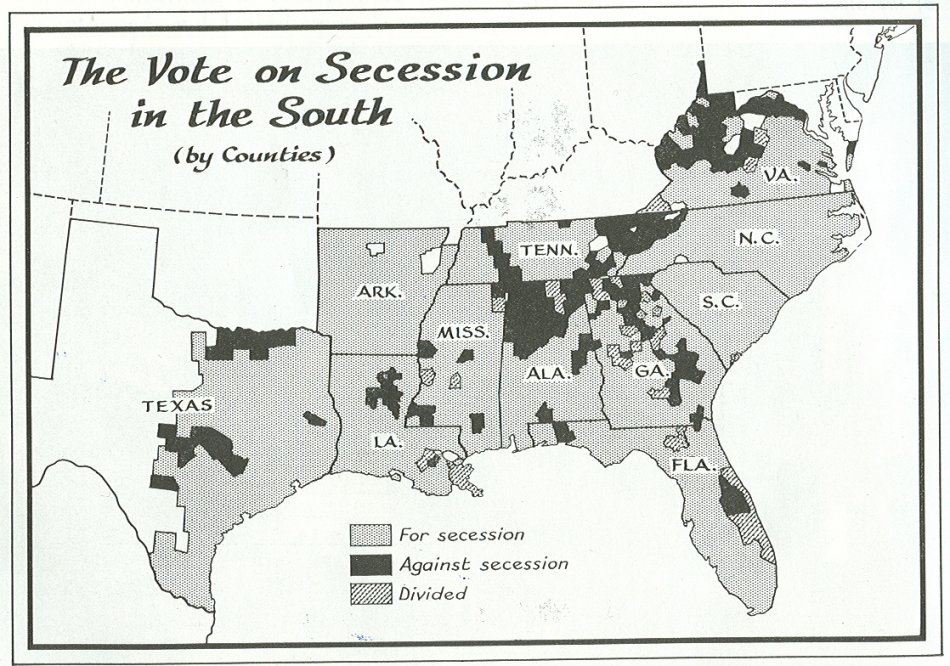

- You sometimes hear arguments that the Civil War wasn’t really about slavery — that instead it was about other issues like states’ rights or excessive federal power. But if you look at which states — and which parts of states — voted for secession, it becomes hard to deny that slavery was a major factor. For example, in Tennessee, support for secession was strongest in the West, where slave ownership was most common. People in mountainous East Tennessee, where slave ownership was rare, were less enthusiastic about the idea. Similarly, slavery was relatively rare in Northern Alabama, and voters there voted against seceding. In Virginia, slave ownership was rare in the mountainous west, which opposed secession and became the separate state of West Virginia.

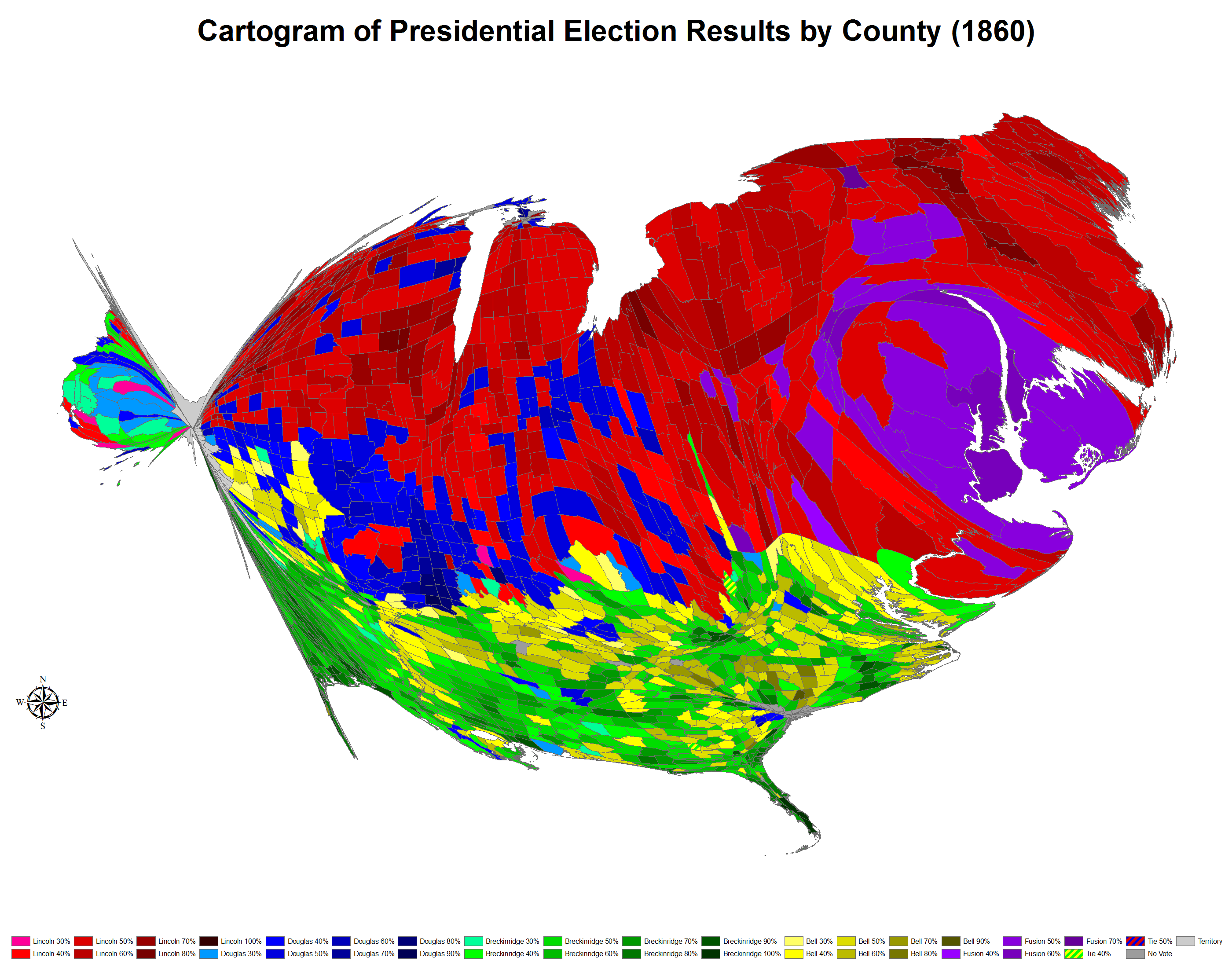

- Every president elected before 1860 had enjoyed at least some support in both the North and South. But by 1860, the rift between North and South had become so great that no candidate or party could bridge it. The national parties that had dominated American politics for decades split along sectional lines. The Northern half of the Democratic Party named one candidate, while Southern Democrats named another. In the North, remnants of the defunct Whig party joined with abolitionists to form the Republican Party, while Southern Whigs joined with nativists to form the Constitutional Union Party. The result was effectively two different presidential races. In the North, Republican Abraham Lincoln (red) defeated Democrat Stephen Douglas (blue). In the South, Southern Democrat John Breckinridge (green) defeated Constitutional Unionist John Bell (orange).

- Obviously, under the Constitution the United States can have only one president. This cartogram illustrates why the winner in the Northern states — Lincoln — became president despite earning hardly any votes in slave states. Today, Florida, Texas, and California are the three largest states in the union, but in 1860 they were so sparsely populated that they barely mattered politically. Instead, the three largest states were all in the North: New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Together, they accounted for more than a quarter of the nation’s electoral votes. Add the staunchly Republican Northeast and the fast-growing Midwest, and Lincoln wound up with 180 electoral votes, far more than the 152 votes he needed for victory.

- Secession had been widely discussed as a remedy to Lincoln’s election during the campaign, but the actual process of leaving the union was rather drawn-out and haphazard. South Carolina went first, on December 20, 1860, stating explicitly that slavery was the reason for the crack-up in its declaration of secession. At the time, new presidents weren’t inaugurated until March and over the course of January and February, the Palmetto State was joined by a swath of other Deep South states. Four states from the outer South — including large and prosperous Virginia — held on, trying to gain leverage for some kind of negotiated settlement. But when hostilities began at Fort Sumter in South Carolina, the Old Dominion and three others left to join the Confederacy.

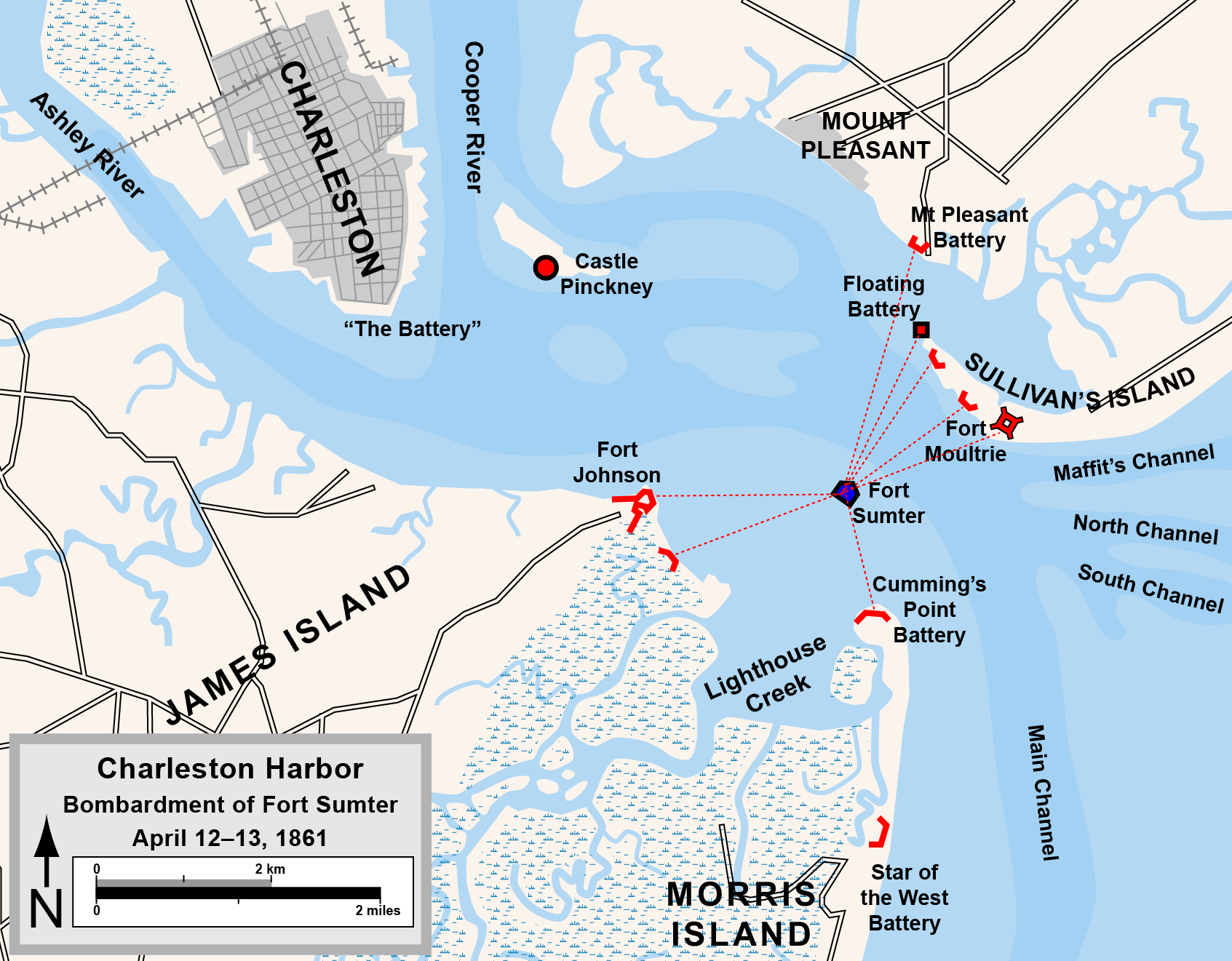

- South Carolina seceded months before Lincoln actually took office in March 1861, creating a dilemma for federal officials in the state — especially the military personnel charged with manning the fortifications that had originally been designed to protect the Port of Charleston from foreign attack. Deeming Fort Moultrie indefensible, Major General Robert Anderson ordered it abandoned, carrying what military equipment he could to Fort Sumter, on an Island in Charleston Harbor. President James Buchanan refused to surrender Sumter to South Carolina, but also declined to take the kind of large-scale military action that would make it possible to resupply the fort. Soon after Lincoln took office, the fort began to run out of food, forcing his administration to act. Lincoln chose to send an unarmed resupply ship, hoping the South would fire the first shot of the war. Confederate officials took the bait, firing on the fort on April 12 and starting four years of war.

- The Union’s great advantage in the war was a substantially larger population and an industrial base that was bigger by an even larger margin. The South simply didn’t have the ability to stand toe to toe with the North over the course of a long conflict. On the other hand, it’s not exactly rare in history for an underdog to win a war of liberation against a larger and richer conquering power. From the American Revolution to Algeria to Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, lightly armed insurgent movements often win wars against mighty powers. But the South did not really adopt an insurgent strategy. Instead, they formed large formal armies and met federal troops in pitched battle. The Confederates hoped this would help them secure international recognition, believed that a few victories would sap northern will to fight, and perhaps also recognized that while guerrilla tactics can be effective at winning wars they are unlikely to be of much use in helping plantation owners retain their mansions and human chattel.

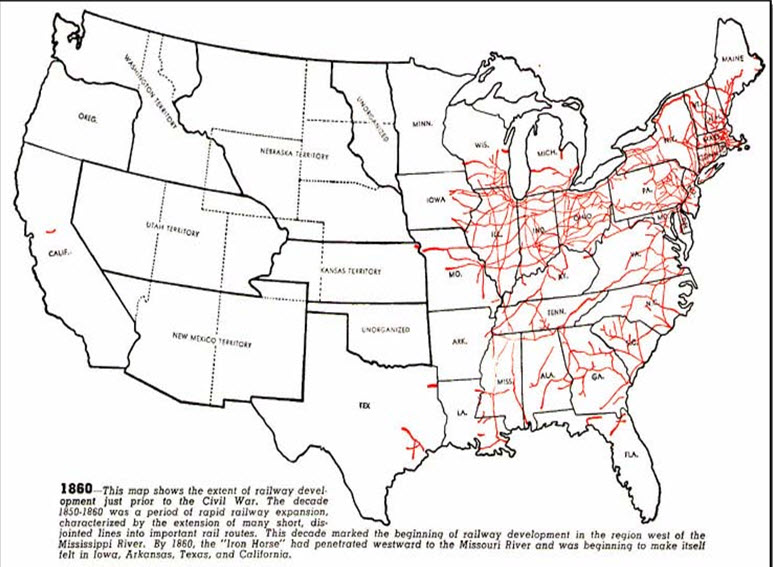

- The much greater density of railroad networks in the Northern states is an impressive visual manifestation of their greater population density and level of industrialization. The rail network helped the Union in concrete terms during the war, because it facilitated the movement of troops and supplies across the very large frontier. But it also signifies a larger set of Northern advantages. Those railroads were useful during wartime, but they existed long before it because the demand for them existed in the form of Northern factories and large Northern cities. The supply chain to create them existed, both in terms of metal and sophisticated financing. The same features of a modern industrial and financial capitalism that gave the North the capacity to construct such a vast rail network gave it formidable advantages in terms of shipbuilding, munitions supply, and other key sinews of war. The key question throughout the duration of the conflict was whether the North would make the political decision to use its resources to crush the South, not whether it had the capacity to do so over the long haul.

- This map offers a very high-level overview of the major land campaigns of the Civil War. One point to note is that the Virginia theater of the war — the one in which Robert E. Lee led Confederate forces and which contains a large share of the war’s most famous battles — was geographically tiny compared with the more open western campaigns. And indeed, though it was Lee’s surrender that ended the war, it was arguably Union victories out west that won it. Long before the Union’s Army of the Potomac succeeded in traversing the relatively short distance between Washington and Richmond, federal forces had overrun the entire length of the Mississippi River and then cut through the center of Tennessee, down through Georgia, and up into the Carolinas. These victories weren’t nearly enough to knock the South out of the war, but the inability of the Confederate government to defend its territory undermined its ability to keep the Army of Northern Virginia supplied, and over time provided the Union with increasing manpower resources in the form of black troops who fled slavery toward the Union lines and then took up arms to fight for their own liberation.

- The much greater density of railroad networks in the Northern states is an impressive visual manifestation of their greater population density and level of industrialization. The rail network helped the Union in concrete terms during the war, because it facilitated the movement of troops and supplies across the very large frontier. But it also signifies a larger set of Northern advantages. Those railroads were useful during wartime, but they existed long before it because the demand for them existed in the form of Northern factories and large Northern cities. The supply chain to create them existed, both in terms of metal and sophisticated financing. The same features of a modern industrial and financial capitalism that gave the North the capacity to construct such a vast rail network gave it formidable advantages in terms of shipbuilding, munitions supply, and other key sinews of war. The key question throughout the duration of the conflict was whether the North would make the political decision to use its resources to crush the South, not whether it had the capacity to do so over the long haul.

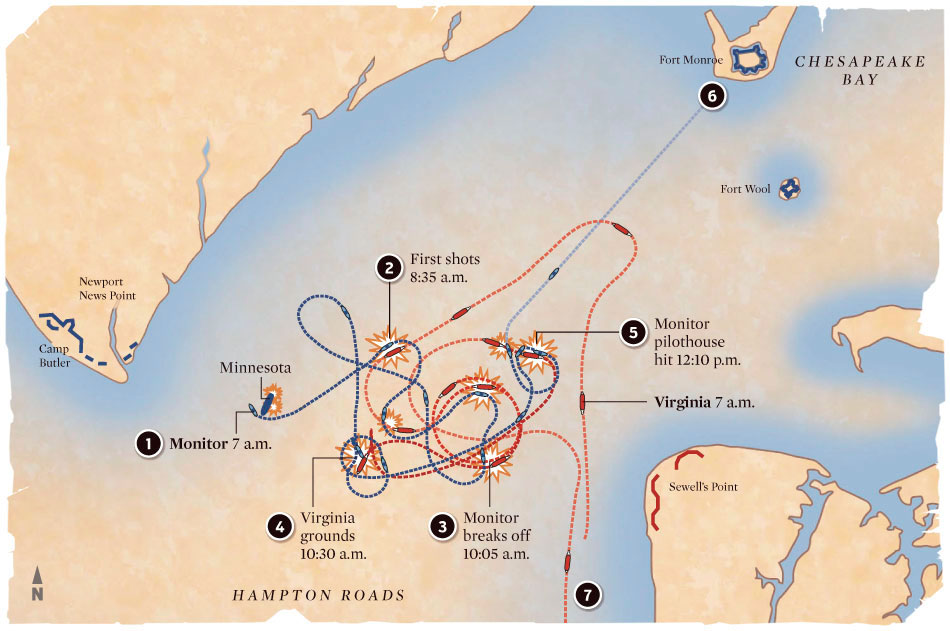

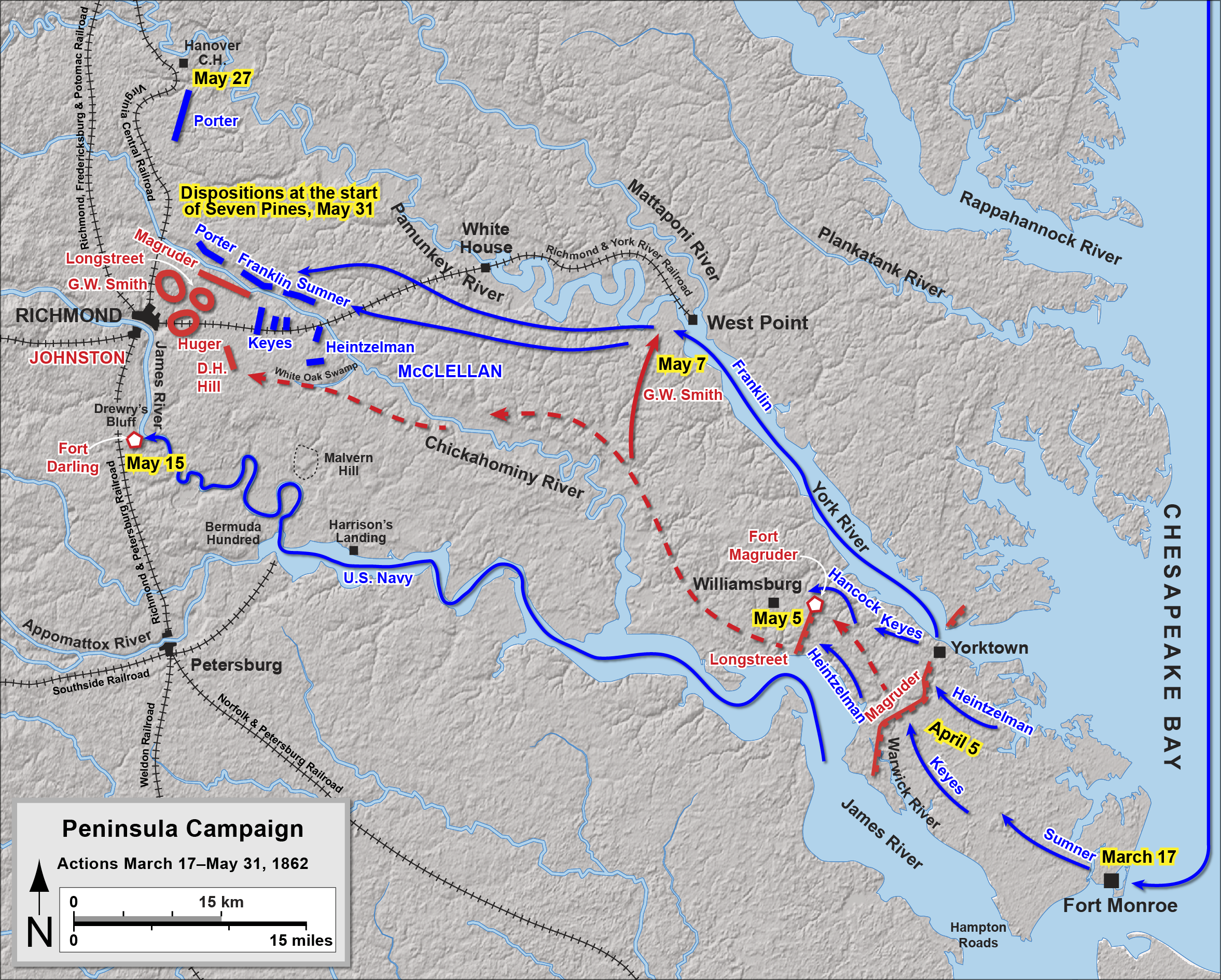

- In 1862, Union Gen. George McClellan set out with more than 100,000 men on a campaign to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. The plan was to sail down the Chesapeake Bay, land on the peninsula between the York and James rivers, and then march 80 miles upriver to capture Richmond. McClellan was charismatic, detail-oriented, and well-liked by his troops. But he had a pathological aversion to risk-taking. The first Confederate troops McClellan encountered, commanded by John Magruder, were well-entrenched, but there were only 13,000 of them. McClellan should have been able to rout them fairly easily. But Magruder put on a show for McClellan, parading the troops past the same point multiple times to exaggerate their numbers and convincing McClellan that the force was much bigger than it really was. So McClellan wasted weeks preparing for the battle. These and other delays gave Confederate forces plenty of time gather reinforcements and prepare their defenses, leading to a series of inconclusive battles in the outskirts of Richmond.

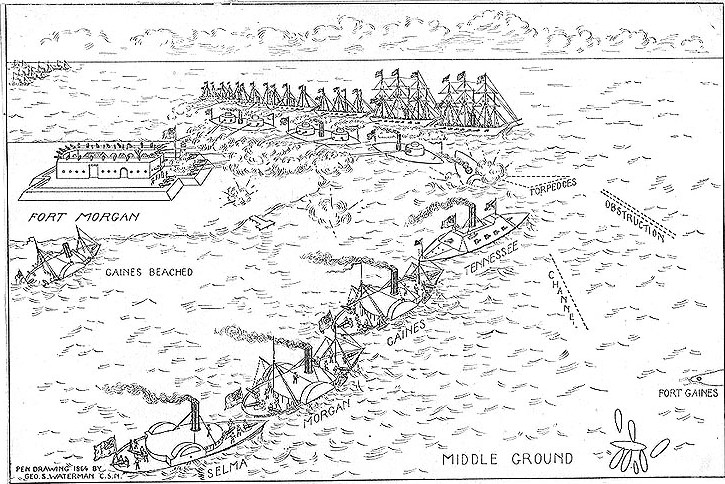

- In addition to running an increasingly successful blockade of the Confederate coast, Union forces also gradually took control of key Confederate ports. By 1864, Mobile Bay was one of the few Southern harbors still in Confederate hands. A fleet led by Admiral David Farragut steamed into Mobile Bay on August 5 in hopes of changing that. After one of his ships struck a mine (also known as a torpedo in the 1860s) that had been laid by confederate ships, the other ships hesitated. According to popular legend, Farragut responded by shouting the immortal phrase, “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead.” We don’t know if Farragut uttered these exact words, but we do know that he pressed his ships forward, skirted the minefield, and gained control of the bay, depriving the Confederacy of one of its last avenues for shipping goods by sea.

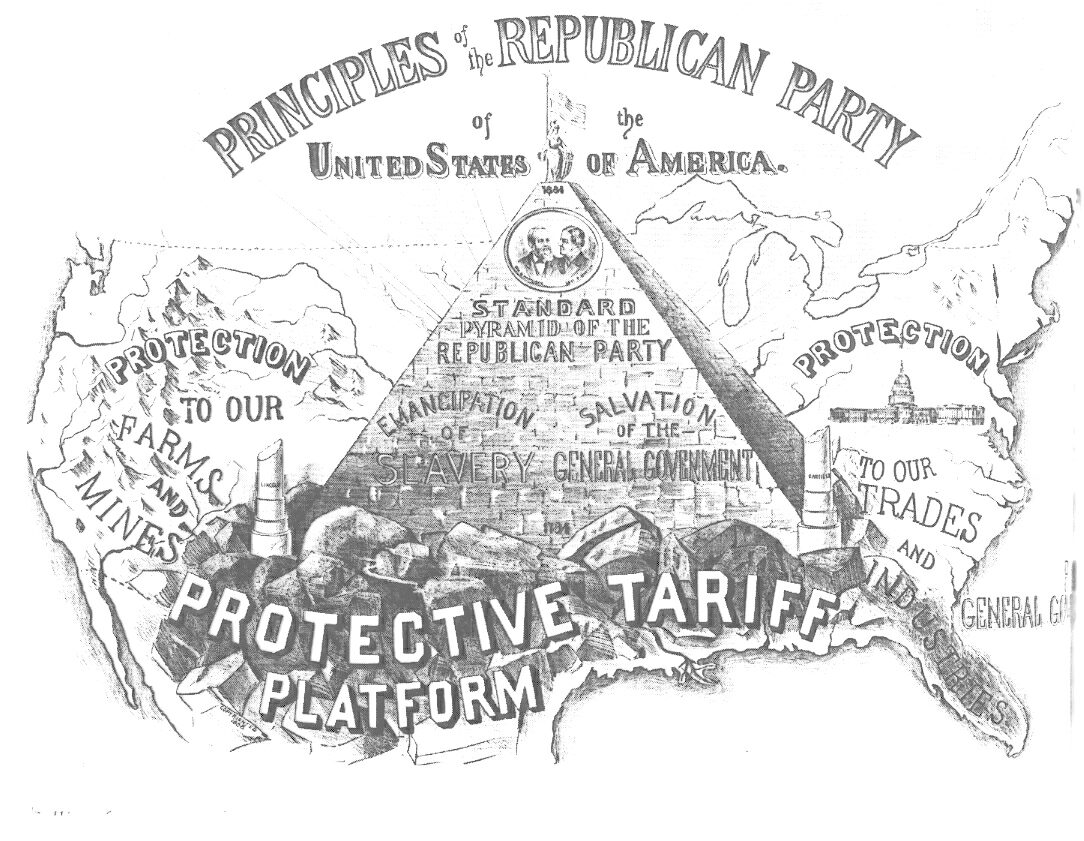

- This map produced for the 1880 campaign season features the Republican Party touting one of the signature achievements of its ascendancy — the protective tariff. Both the Federalist Party and the Whig Party had generally argued for high taxes on imported goods in order to encourage the growth of American industry, but both were typically defeated at the polls by the Democrats. When the new Republican Party came to the fore, anti-slavery ideology was at the core of its appeal, but it retained the old Whig tariff policy. After the South seceded, the GOP suddenly found itself in possession of large majorities. Even before Lincoln took office, Congress passed Vermont Rep. Justin Smith Morrill’s bill to impose a substantial tariff. The tariff question was in part an ideological one about the merits of statist versus laissez faire approaches to economic development, but it also spoke to the regional divide in American politics. The South, with its slave plantations and soil suitable for the cultivation of export-oriented cash crops, benefited from the ability to import low-priced manufactured goods from abroad. Northern agriculture was less commercially promising, and while Northern industry far outpaced Southern industry it lagged behind competition from Britain in many respects. A high tariff essentially forced the transfer of some of the South’s agricultural wealth into the hands of Northern industrialists and factory workers.

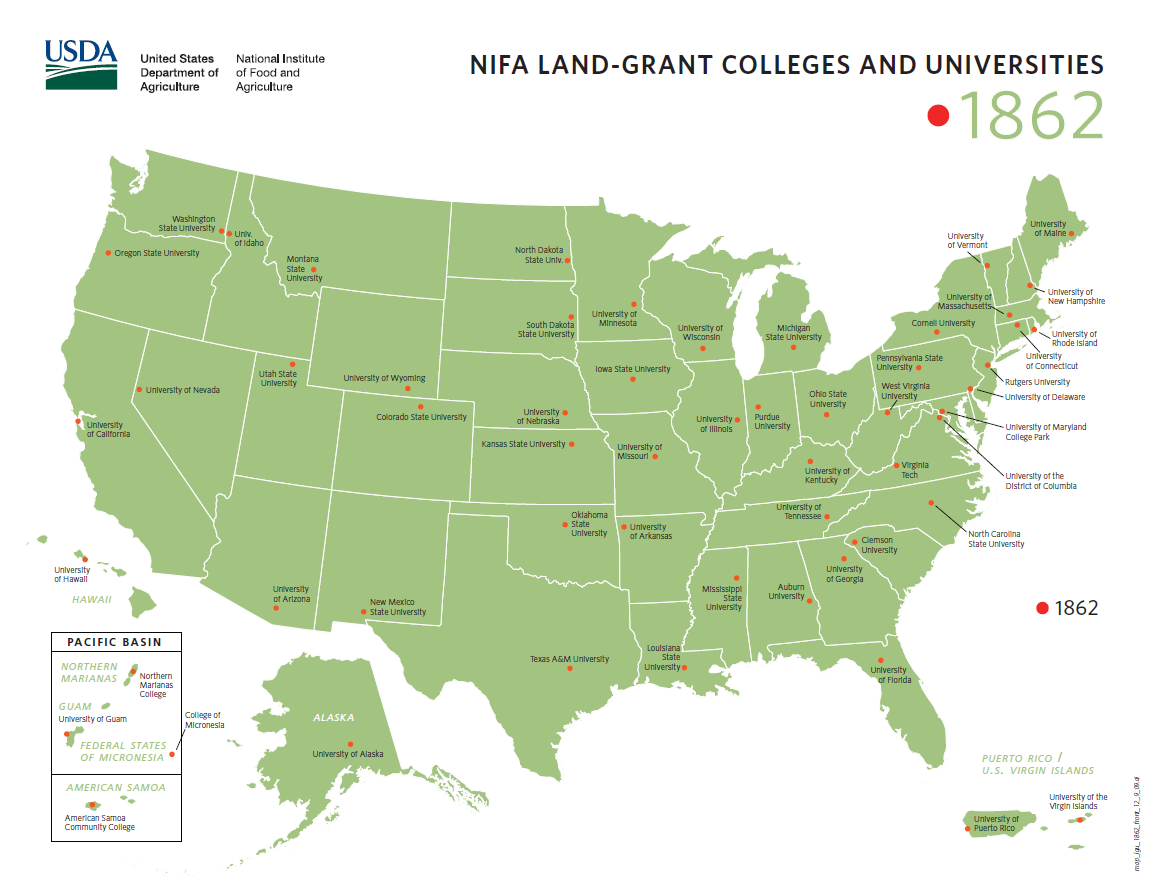

- In 1859, the same Rep. Morrill who would pass the Tariff of 1861 introduced a bill to use federal land to finance institutions of higher education. His idea was that the federal government should make a gift to each state of a big bundle of land, and then instruct the states to use the proceeds of its sale to construct public universities. This was essentially the 19th-century version of a debt-financed infrastructure project, with Morrill calculating that the benefit to future generations of education would be greater than the cost to future generations of foregone land revenue. His bill passed in 1859, but was vetoed by Democratic President James Buchanan. With Lincoln in office, a new version of the same law passed in 1862. Many states have additional public colleges — the University of Texas, Arizona State, etc. — beyond the ones established through Morrill Act grants, but his law remains the historical backbone of public higher education in the United States.

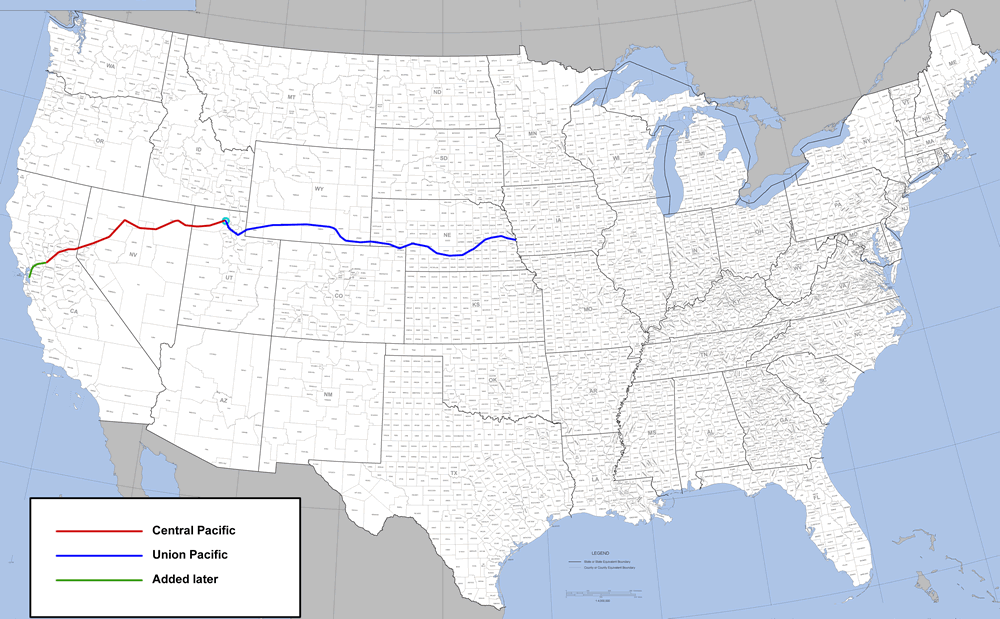

- The idea of a railroad to the Pacific Ocean was at least as old as the influx of American settlers to California. Things really picked up steam when the War Department, under the leadership of then–Secretary (and later CSA President) Jefferson Davis published an exhaustive multi-volume report detailing five possible routes. But congressional gridlock made it impossible to choose which route to take. With Davis’s strong encouragement, Franklin Pierce’s administration had purchased a swath of land from Mexico comprising what is now southern Arizona and southern New Mexico that would have facilitated the creation of a Southern-oriented version of the Pacific Railroad and encouraged settlement in territories that were open to slavery. Northern members generally favored the so-called “central” route that was eventually selected. With the departure of Southern legislators during the Civil War, the gridlock was broken, and the Pacific Railroad Act provided free land and subsidized loans for the construction of the railroad.

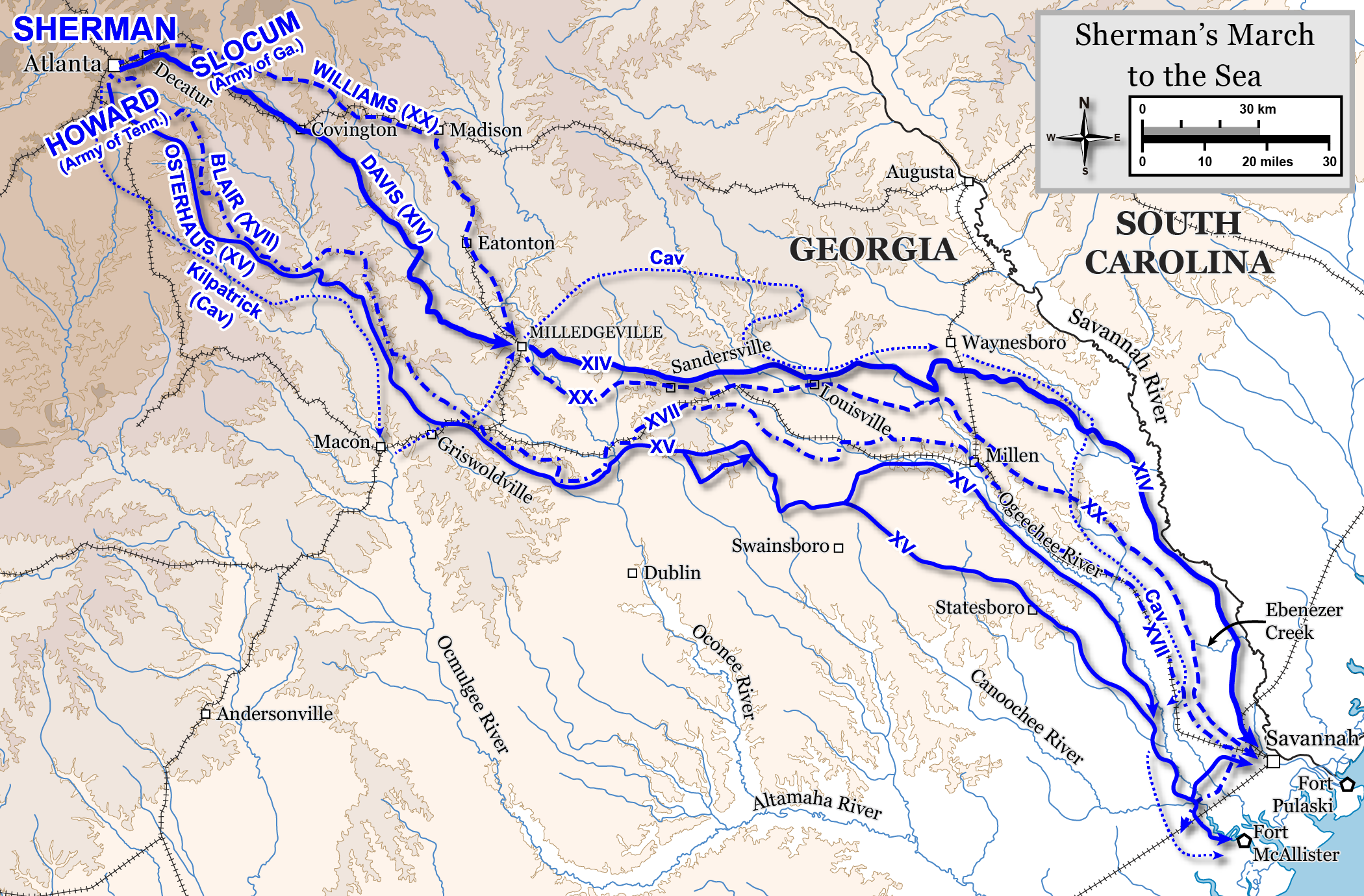

- In the summer of 1864, Confederate General Joseph Johnston was fighting a war of attrition in the South that in many ways previewed the trench warfare of World War I. He would force the Union soldiers to attack entrenched Confederate troops, inflict heavy casualties on Sherman’s men, and then retreat to a new defensive position to repeat the whole process again. Meanwhile, Sherman was forced to deploy soldiers (and suffer serious casualties) in the rear defending rail lines from Confederate raids. By the time he captured Atlanta in September, Sherman was tired of this. So he marched 60,000 troops away from the Confederate troops and toward Savannah, Georgia. The Union army cut a wide path of destruction through the Georgia countryside that was 25 to 60 miles wide. They destroyed railroads, burned down buildings, and freed slaves. Instead of shipping food in from the North, they ate food taken from Southern farms and warehouses. Sherman’s march sapped both the will and the capacity of the South to carry on the war.

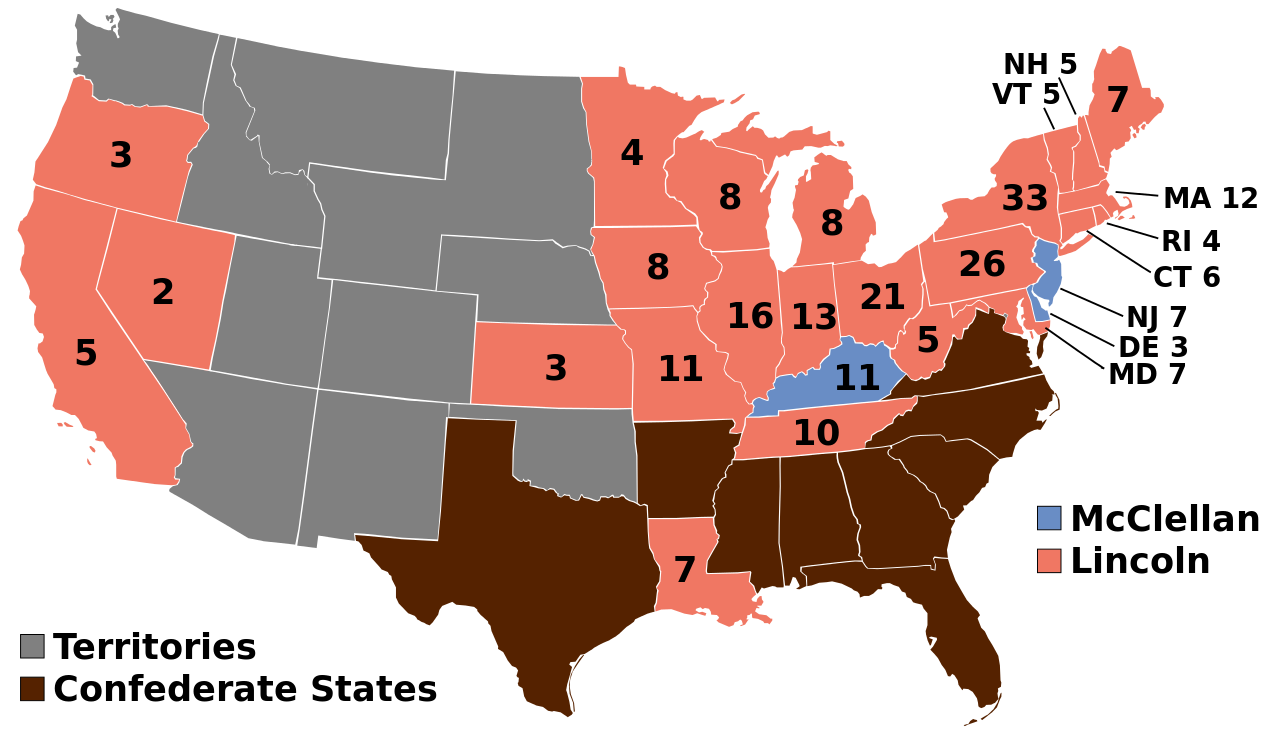

- Abraham Lincoln was reelected decisively in the 1864 election (the states he won are in pink here). But his reelection was hardly a foregone conclusion. In August 1864, Lincoln himself believed he would likely lose to George McClellan, the Democratic candidate and Union general Lincoln had fired for excessive timidity. Many thought that if McClellan won, he would bring the war to a quick conclusion by recognizing Confederate independence. But Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in September boosted Union morale and with it Lincoln’s reelection chances. The 1864 election also brought to office Vice President Andrew Johnson — a pro-war Democrat Lincoln put on his ticket as a gesture of national unity — and an even-more-Republican Congress. When Lincoln was shot in April 1865, Johnson became president. The moderate Johnson clashed frequently with Republicans in Congress who favored vigorous efforts to protect the civil rights of newly freed slaves.

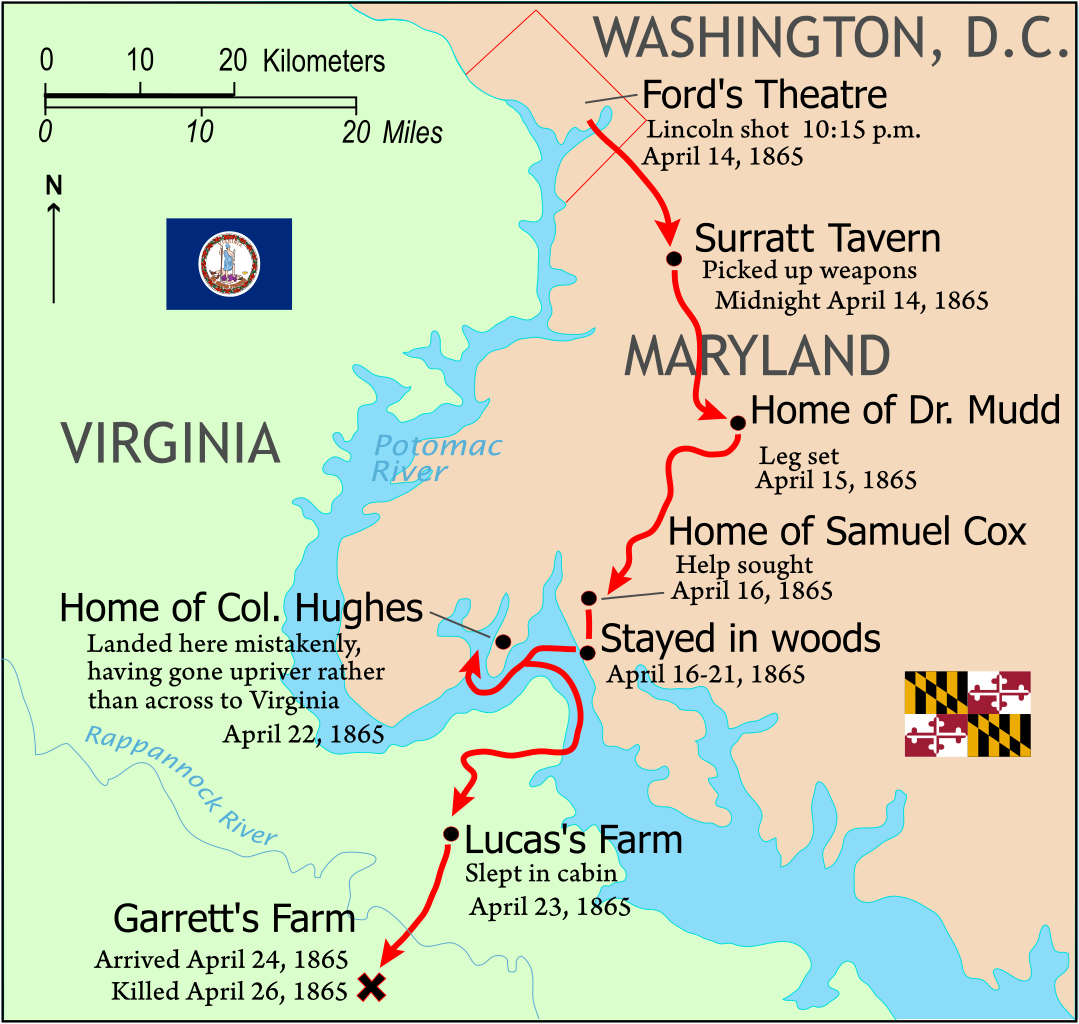

- John Wilkes Booth was a well-known Washington actor with Confederate sympathies who hatched a plot to assassinate President Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, he slipped into Lincoln’s box at Ford’s Theatre and fired a fatal shot into Lincoln’s skull. Booth’s fame allowed him to slip into the box without arousing suspicions. And he knew the play Lincoln was watching, Our American Cousins, so well that he could predict when audience laughter would be loud enough to mask the sound of the gunshot. This map shows what happened next: Booth escaped from Ford’s Theatre and was able to evade the Union manhunt for more than a week, staying with several people as he fled south. Union troops finally found him hiding in a barn on April 26. He was shot by a Union soldier during the resulting standoff. The assassination changed the course of US history by replacing Lincoln with the relatively Confederate-friendly Andrew Johnson. Ironically, a Booth co-conspirator, George Atzerodt, had been assigned to kill Johnson, too, but Atzerodt lost his nerve and never carried out the attack.

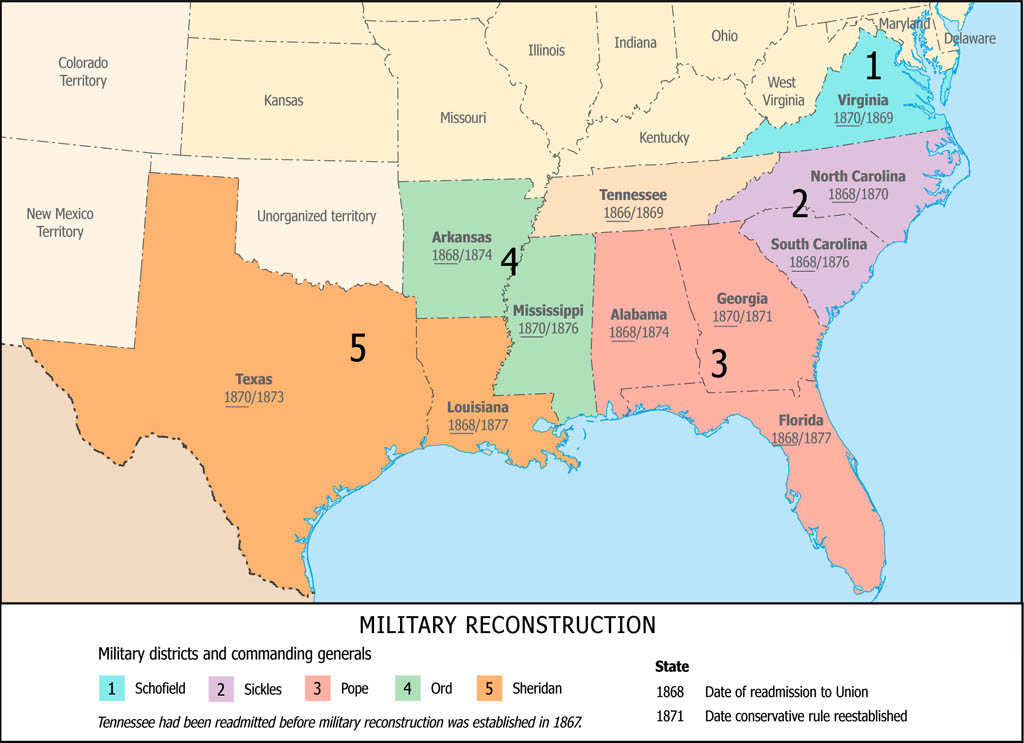

- After the war, Congress divided the former Confederacy into five military districts and set criteria for states to apply for readmission to the Union. This map shows the military districts, the year of reentry into the Union, and the year on which white-dominated government was restored (which Southerners described as “redemption”). As you can see, the Reconstruction experiment was relatively short-lived in most states, and for many decades the dominant Dunning School of historians held that it was a mistake. The civil rights movement in the mid-20th century induced a reconsideration of these views, and Reconstruction is now broadly seen as a worthy and temporarily successful stab at social justice that was undone by a mixture of Southern white violence and Northern white indifference.

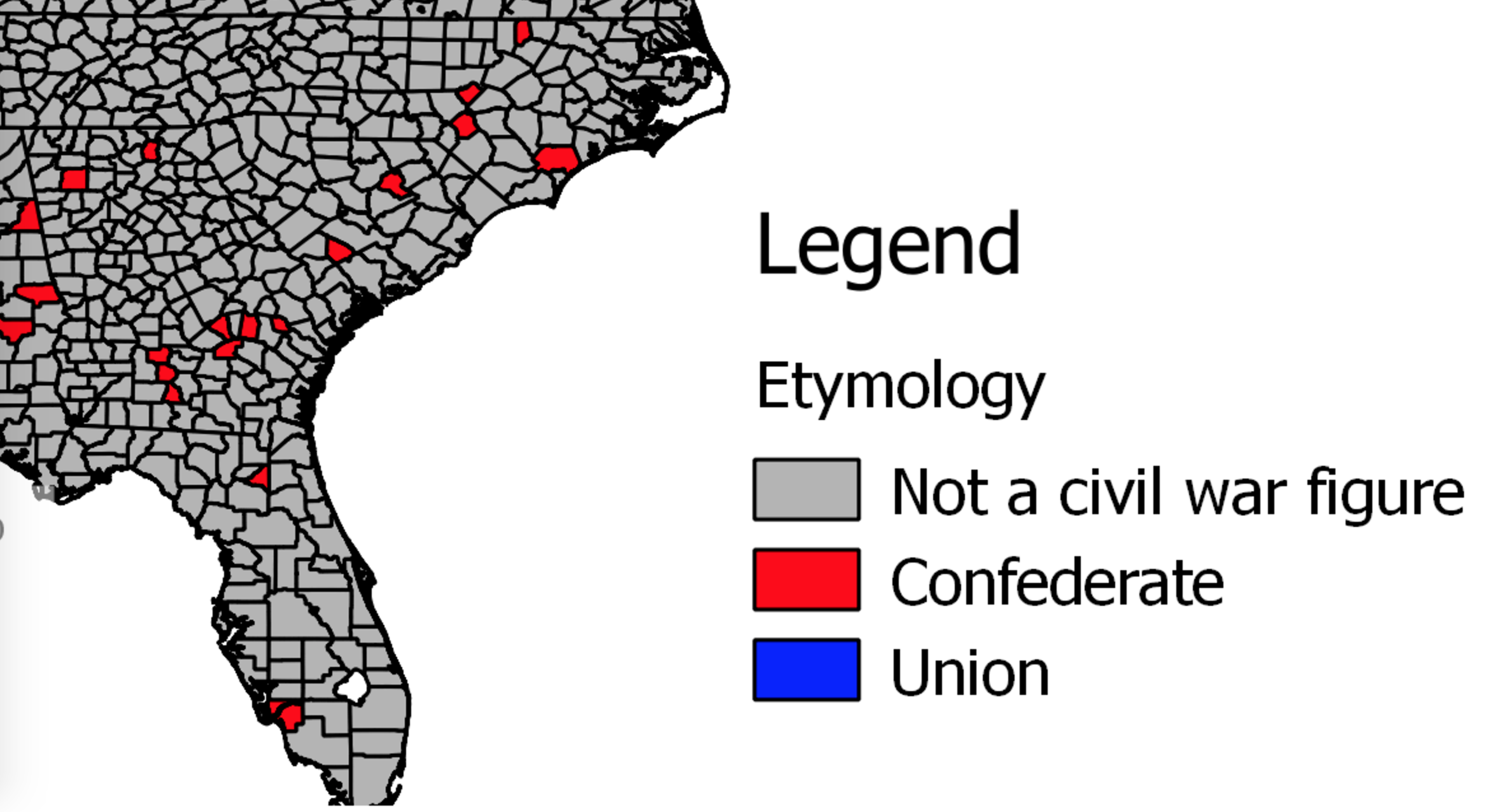

- One sign of the Civil War’s ambiguous legacy in the United States is the large quantity of official facilities named after generals or politicians who served at high levels of the rebellion. This map shows in red the counties named for Civil War figures (click for a full map with legend), which illustrates that throughout the South the rebel leaders are officially regarded as heroes worthy of celebration rather than traitors who fought for a cause that Ulysses Grant called “one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.” The counties themselves are, of course, just a drop in the bucket. Mississippi is represented in Statuary Hall in the Capitol Building by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. There are even federal military bases named after Confederate generals.

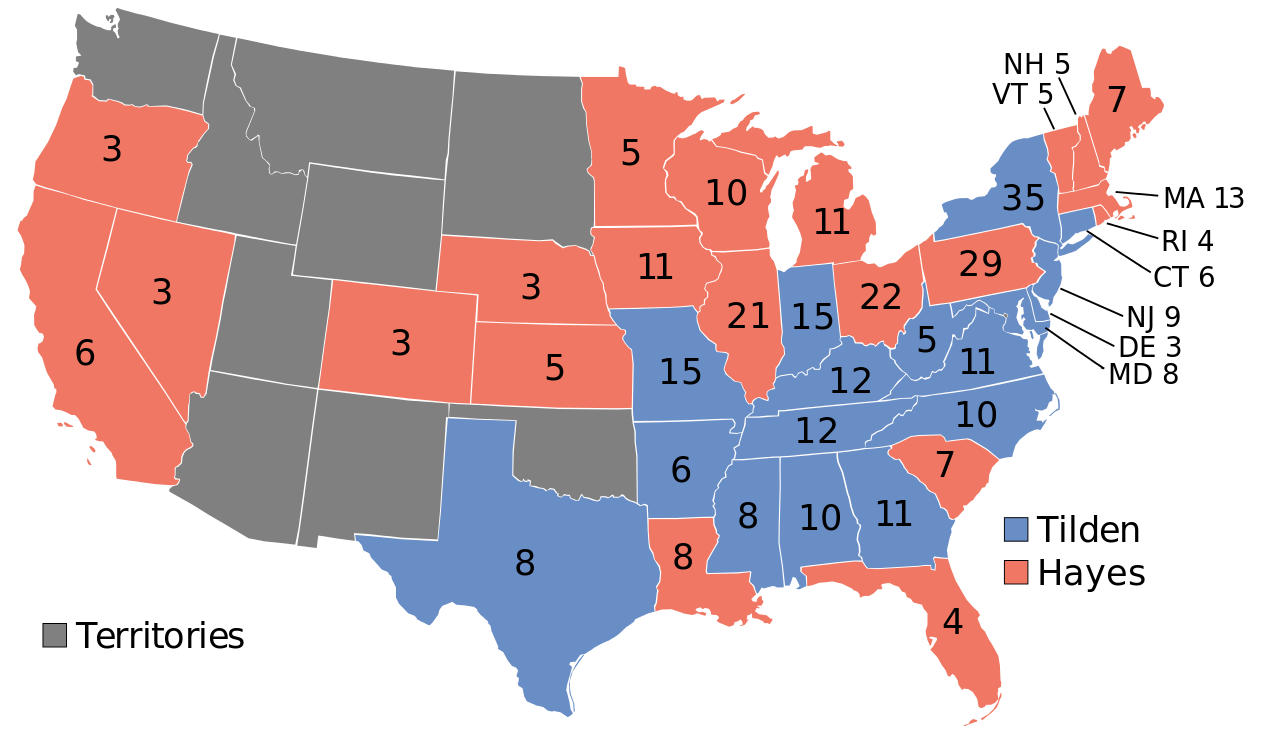

- Democrat Samuel Tilden’s narrow 1876 win in Indiana — a state that had voted Republican in every presidential election since 1860 — left Republican control of the White House dependent on the electoral votes of three Southern states that were still under military occupation. Republicans claimed wins in all three, but Democrats charged fraud. The issue was eventually settled by a compromise brokered in Congress. Democrats would accept the legitimacy of the Republican counts in the Southern states, but in exchange the new President, Rutherford B. Hayes, would withdraw federal troops from the South and end Reconstruction. The deal left Southern governance squarely in white supremacist hands. With black voters disenfranchised no Republican would carry a Southern state again until Herbert Hoover in 1928. For 50 years or so after the 1876 election, Republicans remained the party that was more supportive of black interests, but they seriously downplayed the issue. With the western frontier definitely secured for free white labor, the element of the anti-slavery agenda that had broad electoral appeal to Northern whites was already off the table.

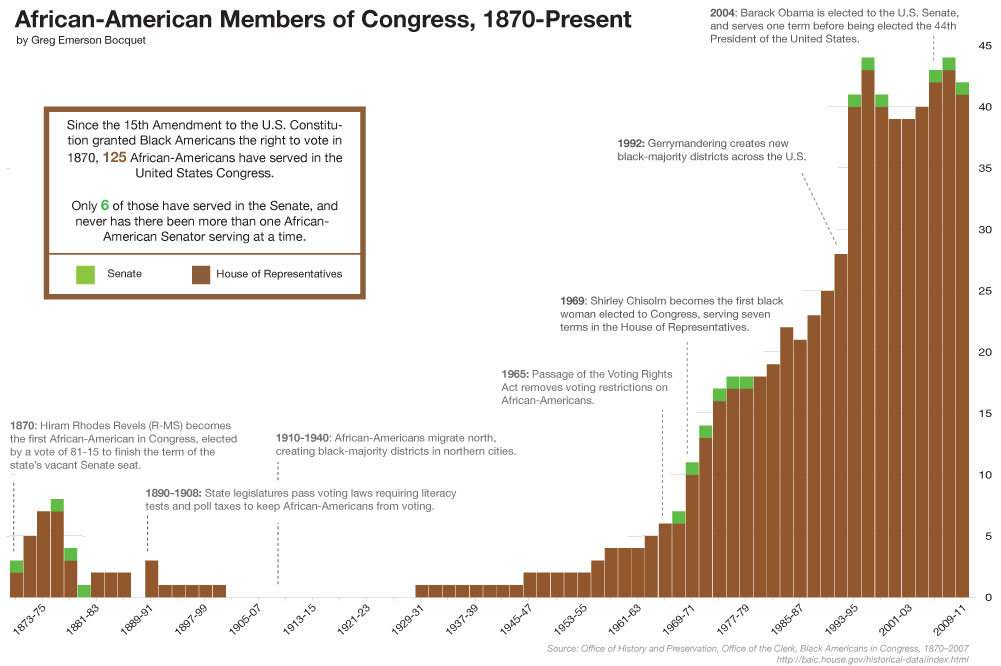

- Reconstruction led to an unprecedented surge in African-American representation in the United States Congress, as liberated slaves found themselves in the majority in a number of districts across the South. As Southern state governments were “redeemed” by white Democrats — and especially after Rutherford Hayes’s election led to the withdrawal of federal troops — gerrymandering and voting restrictions were put in place to curb black representation. African-American congressional representation scored a minor comeback in 1890 that was countered by a renewed drive to disenfranchise black voters through a wave of new state constitutions that in many cases also disenfranchised many lower-income white voters. A fusion movement between the GOP and the then-burgeoning Populist Party led to George Henry White’s 1896 election in North Carolina, and he served two terms as the lone black member of Congress. In 1898, the Democrats recaptured the state legislature on a white supremacy platform and passed an effective disenfranchisement bill in 1900, and White resigned. “This is perhaps the Negroes’ temporary farewell to the American Congress, but let me say, Phoenix-like he will rise up some day and come again,” White predicted in his final speech. In 1928, Oscar de Priest entered the House from a Chicago district and proved White correct.

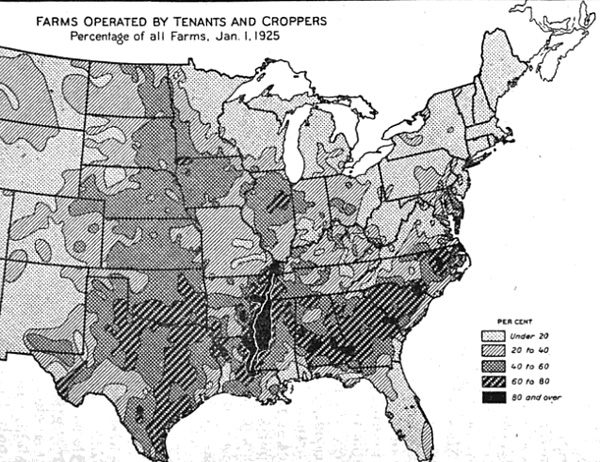

- The Civil War freed the slaves, and Reconstruction temporarily granted them basic political rights. But the settlement of the war made no provision for land reform or economic redistribution. The federally owned land of the West was secured for free (largely white) owner-operated farms, but the basic underpinnings of the Southern plantation economy were left intact. Newly freed slaves owned no land or farm equipment, and had little in the way of formal education. With Southern governments from the 1870s onward uninterested in providing any of those things, most of the rural black population was forced into a particularly unremunerative form of tenant farming known as sharecropping. In exchange for land to till, seeds to plant, and basic equipment, the sharecropper would do all the work and hand a large share of the proceeds over to the landowner. Discriminatory enforcement of laws against “vagrancy,” barriers to education and the professions, and discrimination on railroads and other public accommodations made it exceptionally difficult for sharecroppers to move from job to job or bargain for better conditions. Over time a “Great Migration” to industrializing Northern cities began to provide an exit option, and then the post–World War II industrialization of the South began to undermine the sharecropping system even as the Civil Rights Movement began to gather steam.